I sat down today to writer something far deeper and richer about the history of incense in China, but realized that I couldn’t do it without some basic explanations upfront about… Chinese.

Yes, Chinese. It is a complicated and confusing language. Not the least because the language itself is inherently one of the most difficult to learn. But also because there are different dialects, different character forms, and all different ways of romanizing (ie, converting Chinese into letters to use in English or other Latin-based languages).

So before we get into incense, I decided to clear the air on Chinese - some simple facts, and why we decided to include it on our website. If you're reading this for a quick key to the Kin way of writing nouns, scroll down to the middle for the section in red.

Otherwise, here we go -

What are the different types of Chinese? And why do they exist?

Great, let me break it all down into basics.

First: The China Region

The “China region” consists of The People’s Republic of China (mainland China), Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. Historically these were a single country with a single Government, but for complicated political reasons they no longer are. So China as it is most commonly used refers to mainland China.

Each part of the China region uses a different combination of spoken and written Chinese.

Second: Mandarin vs Cantonese

Fact 1:The China region is large, and has many regional dialects. The two most dominant historically were Mandarin (originating from the north, spoken by mandarins in the palace) and Cantonese (originating from the south, spoken in the popular trading province of Canton).

Fact 2: In 1911, Mandarin was elected as the official spoken language of China. It remains the official spoken language of mainland China and Taiwan today, and is by far the dominant spoken Chinese.

Fact 3: Cantonese retains some importance as the official spoken language in Hong Kong and Macau, it is also common in overseas Chinese communities, especially through South East Asia.

Third: Simplified vs Traditional Written Chinese

Fact 4:All spoken Chinese can be written the same way. The form of characters used up until the 1950s is called Traditional Chinese, where as the form introduced in mainland China in the 1950s is called Simplified Chinese. Simplified Chinese was introduced to help boost literacy levels, and as the name suggests, simplifies the traditional characters so they are easier to remember. Most characters in Simplified Chinese have fewer strokes than Traditional Chinese, but some did not change.

Fact 5:Simplified Chinese characters are used in mainland China, and traditional Chinese characters have been retained by Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Forth: Romanizing Chinese into English

Fact 6: Due to Canton’s early status as an international trading centre, Cantonese was used internationally for converting Chinese into English until the last few decades. History books contain many Cantonese versions of names eg, Peking vs Beijing (old Cantonese romanization vs today's official Mandarin romanization).

Fact 8:A system called Wade-Giles for romanizing Mandarin was introduced in the 19th century. This system is now largely redundant, although Taiwan still uses it for place and personal names. It is also common in history books, and retained in many overseas Chinese names.

Fact 7: The defacto official system used for romanizing Mandarin is now Pinyin. Pinyin was introduced as a supplementary alphabet system to help with pronuncing and romanizing Mandarin in mainland China in the 1950s. Pinyin consists of combination of letters for every Chinese character, to indicate how it should be pronounced.

And if all of the above is too difficult, just remember that China today uses Mandarin, alphabet pinyin and simplified Chinese characters. These are the defaults that we will assume. Everything else exists for complicated historical and political reasons.

The Kin key to English and Chinese Nouns

Before we get too far into this article, I want to introduce the Kin key for English and Chinese nouns. This is how we will be showing many of the key nouns in our other articles:

English (Simplified Chinese / Traditional Chinese*)

*Traditional Chinese omitted if same as simplified Chinese

Our default when only one set of characters is shown is Simplified Chinese. We decided to include Traditional Chinese in most cases because our readership is skewed towards international Chinese communities, for whom this format will be easier to read.

A couple of examples are below:

1. Incense clock (香钟/香鐘)

English and two formats of Chinese characters shown

2. Aloeswood (沉香)

English and 1 format of Chinese character shown, Simplified and Traditional Chinese are the same for this particular word

Why are we explaining Chinese to you?

Now that we have clarified Chinese, I’m going to bring us back to why we decided to use it on the Kin website.

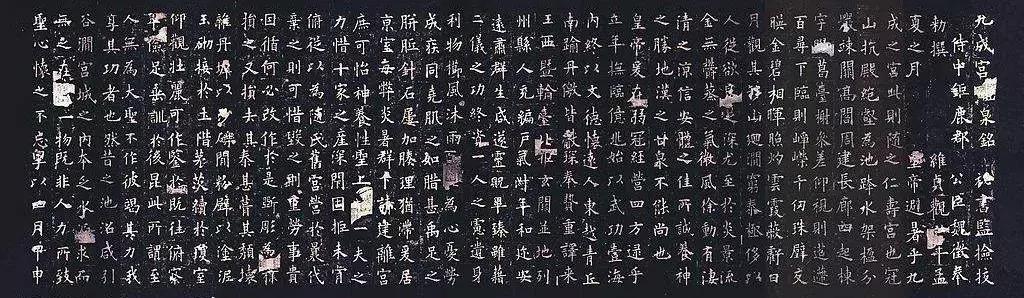

A big part of what we want to do at Kin is make traditional Chinese culture relevant again. We believe that there is incredible richness and wisdom in it, and that we’d all be better off knowing them. Unsurprisingly, a lot of the culture is entrenched in the language. So as we tell these age-old stories, we want to also bring some of the language to you, partly because they showcase the intricacies of certain points, and partly because some of the characters are just really cool. A single Chinese character can say a thousand words.

We also want to use both English and Chinese because for those of us who have some background in Chinese, it is really helpful for crossing the Noun Chasm.

What is the Noun Chasm?

Growing up partly in China and partly in Australia, I learnt Chinese and English in very different contexts. For lack of a better example, let’s me demonstrate with tree names (a very real problem in my life until recently!)

I learnt the Chinese name for trees mostly from evening strolls with my grandfather while in first or second grade. In particular, there were many liushu (willow, 柳树) in China, so that was imprinted in my Chinese-tree vocab. I learnt the English names for trees mostly in high school in science class. Australia was Eucalyptus country, so there were many images of Eucalyptus in my textbooks, and that was key to my English-tree vocab.

But because of the very different contexts and associations, the two sets of tree vocab never connected with each other. I knew the word liushu, I knew the word willow, I would use one word in China, and use the other in Australia. But I never realized they were the same thing, until I used the wonderful tool of Google Translate a few years ago.

I’m not sure why this is, but I think most of us who grow up in bi or multi-lingual families experience this – that’s what leads to those occasions when we can only seem to express something in one language, even though we are perfectly fluent in the other.

I also noticed that this happens much more often with nouns, so that is why I decided to call this seemingly strange occurrence the “Noun Chasm”.

Bridging the Noun Chasm

For me, it’s been super interesting crossing this Noun Chasm, especially as I research Chinese history and culture (I permanently have Google Translate open when I do this).

Chinese history is told with a very different perspective and tone depending on the language we read, so it’s been fascinating piecing English and Chinese together. I don’t think either is better, and I find it really interesting to read both. And fortunately, I have a unique enough set of experiences to balance them, and tell a more nuanced story to you. So that is what we want to do at Kin.

Well, we hope this has been useful, we are always interested in what you think about our stories and our products. We’d also love to hear about your unique Chinese-hyphenated experiences and how you balance them. Please drop us a line and become a Kin family member to stay connected!

Leave a comment (all fields required)